The Waschzettel of Croatian Dante: Marulić's Repertorium and marginalia

A paper for the “Texts Worth Editing”

Seventh Annual Conference of the European Society for Textual Scholarship

Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Pisa

25-27 November 2010

Neven Jovanović

University of Zagreb

Text of oral presentation is here: 101122pisa-jovanovic-ests.html.

PDF of the handout is here: 1011jovanovic-ests-handout.pdf

Abstract

Marko Marulić (Marcus Marulus, Split, 1450--1524) is considered the first great author of Croatian literature. He composed an epic poem in Croatian (Judita, 1501) and two Europe-wide early modern best sellers in Latin (De institutione bene vivendi and Evangelistarium). Marulić styled himself as a Croatian Dante; in Croatia after 1848 he is regarded as a national icon. Even so, one of his Latin works, surviving in an 800 pages long autograph manuscript, was not published until 1998.

Existence of this work, the Repertorium, was signalled to the scholarly community in 1923. And yet the lucky discoverer, the historian Ferdo Šišić, succinctly judged that “it would be absolutely pointless to publish” the text. This verdict seems to have been approved for 75 years, even among Croatian literary scholars. What could have been the reasons?

Today we realise that there are even more Marulić's texts, written in his own hand, that are not even considered for publication. These are marginal notes in books from his library. It is true that the marginalia are neither independent writings, nor do they belong to conventional literary genres. But — bearing in mind the notorious Waschzettel of Schiller and Goethe — in the case of a national classic, any text could be considered important. What can be done in the time of limited resources, in a small country and a small culture?

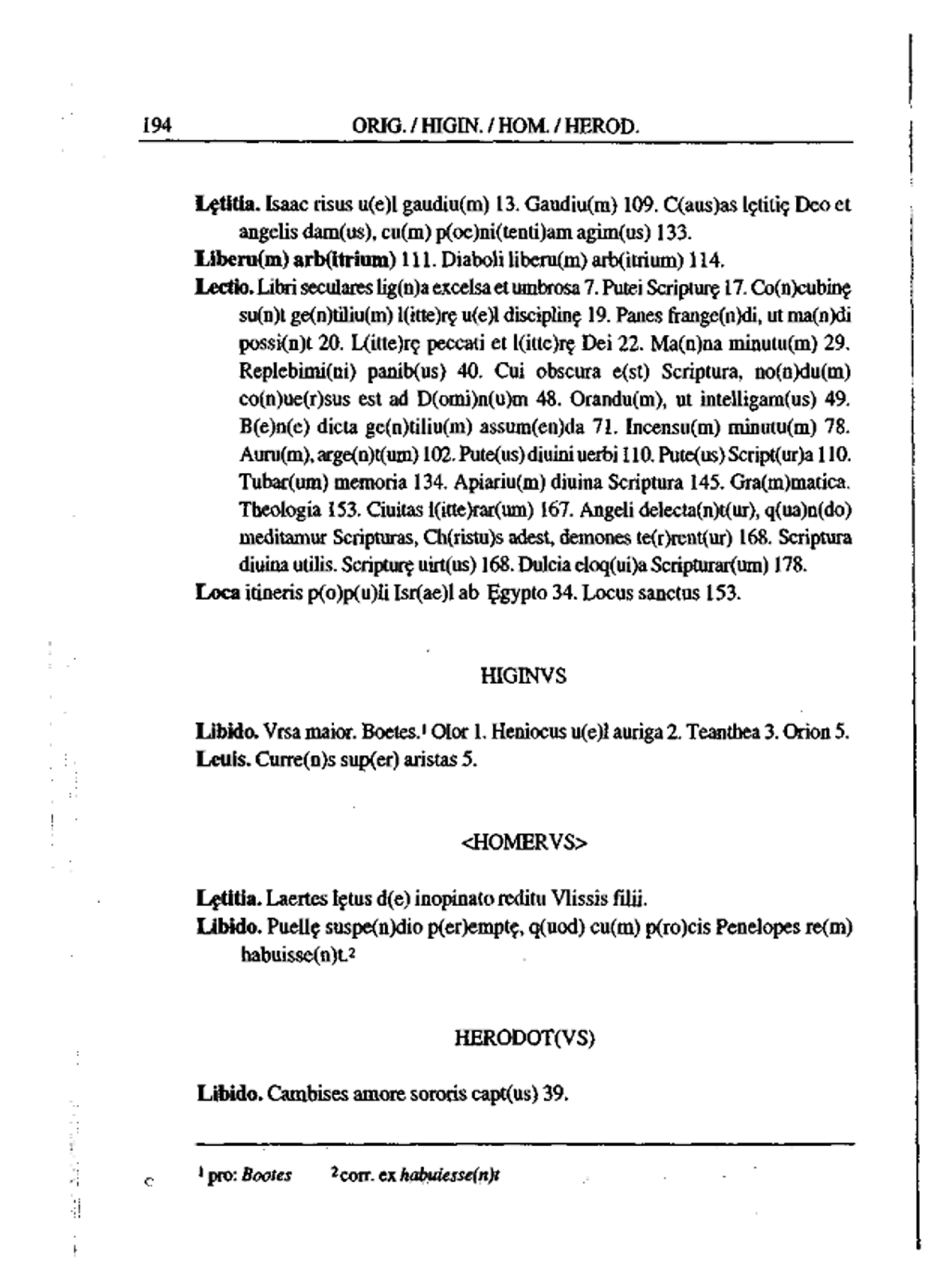

Marulić, Repertorium, f. 233v–234r

Repertorium 1998

Repertorium and Opera omnia

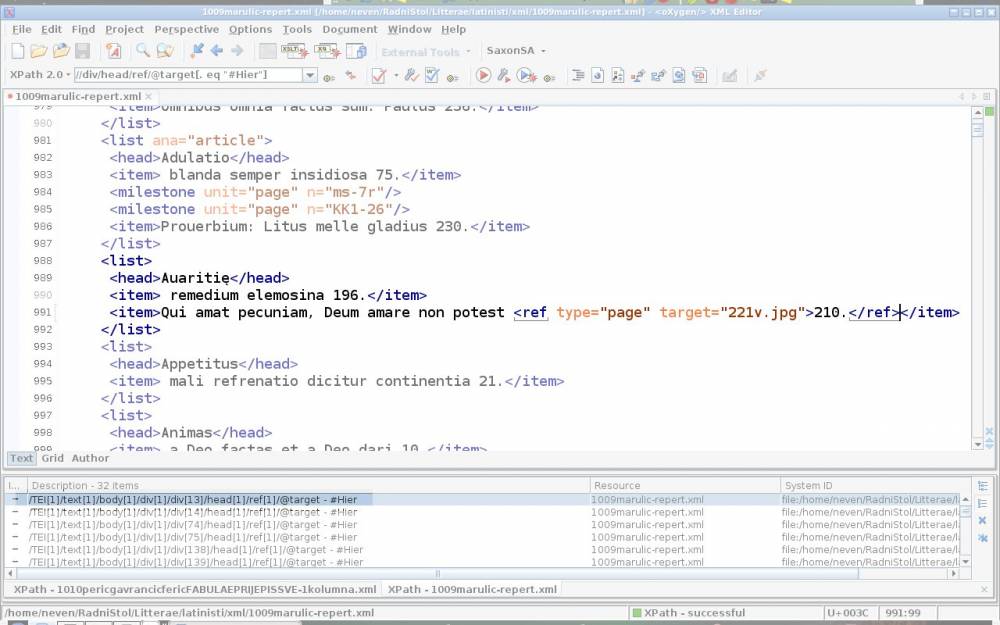

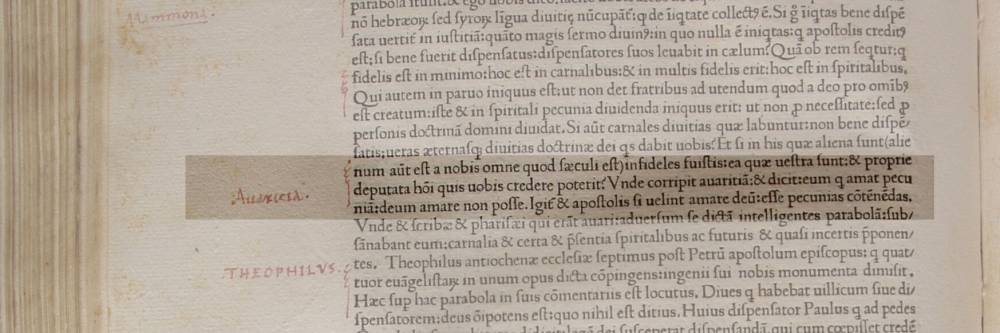

- Qui amat pecuniam, Deum amare non potest (Hieronymus, Epistularum pars prima)

- Repertorium, f. 7r:

- A TEI XML fragment:

- Hieronymus, Epistulae, pars I, Parma 1480 (Marulić's copy):

- A search on pecun* and deu* in Marulić's Opera omnia (CroALa)

Some other searches

- Manna and man: A CroALa search in Marulić's Opera omnia

- Adulatio blanda: another search

Reordering the Repertorium

Via XSLT stylesheets 1 and 2.

Select all quotations listed under “Hyginus” (obviously the Poeticon astronomicon, perhaps the 1512 or 1517 edition by Melchior Sessa & Petrus de Rauanis, publishers of the 1516 Euangelistarium?).

Sort the quotations according to references, which are probably not page numbers.

| Serpens mala aurea custodiens . | ref: 1 |

| Circa Herculem lapidibus pluit, quibus ille inimicos conuertit in fugam . | ref: 1 |

| Serpens horti Hesperidum custos . | ref: 1 |

| Lycaon . | ref: 1 |

| Canis prę dolore defecit. Orpheus lugens Euridicen . | ref: 1 |

| Corona Ariadnę . | ref: 1 |

| Vrsa maior. Boetes. Olor . | ref: 1 |

| Hercules multitudine oppressus geniculauit . | ref: 1 |

| Lyra a Mercurio facta . | ref: 1 |

| Corona a Vulcano facta . | ref: 1 |

| Caduceus insigne pacis . | ref: 1 |

| Engonasim. Peruigil draco . | ref: 1 |

| Andromede, Perseus . | ref: 2 |

| Orpheus . | ref: 2 |

| Hercules ab Omphale donatus . | ref: 2 |

| Capra Iouis et hedi . | ref: 2 |

| Prometheus Iouem decepit . | ref: 2 |

| Andromeda, Casiopeia . | ref: 2 |

| Prometheus ignem de cęlo furatus . | ref: 2 |

| Andromeda Perseum secuta inuitis parentibus . | ref: 2 |

| Rex in Triptolemum . | ref: 2 |

| Heniocus uel auriga . | ref: 2 |

| Perseus. Hercules . | ref: 2 |

| Rex Triptolemo insidiatur . | ref: 2 |

| Triopes templum dirruit, ut suas ędes tegeret . | ref: 2 |

| Cistella Mineruę . | ref: 2 |

| Sagitta Apollinis cum frugibus . | ref: 3 |

| Delphin in cęlo . | ref: 3 |

| Aquila . | ref: 3 |

| Promethei iecur aquila exedens . | ref: 3 |

| Symphonia . | ref: 3 |

| Delphin . | ref: 3 |

| Teanthea . | ref: 3 |

| Symphonia . | ref: 3 |

| Bellorophon Chimeram uicit . | ref: 3 |

| Amphitrite uirgo. Bellorophon . | ref: 3 |

| Pegasus . | ref: 3 |

| Teanthea prodens secreta in equum uertitur . | ref: 3 |

| Prometheus soluitur . | ref: 3 |

| Castor et Pollux . | ref: 4 |

| Asini . | ref: 4 |

| Rugitus asinorum . | ref: 4 |

| Hyades et Pleiades . | ref: 4 |

| Aries Phrixi . | ref: 4 |

| Crines Beronicę . | ref: 4 |

| Leo Herculis . | ref: 4 |

| Vrsa. Artiphilax. Corona, id est Deltoton, sydus triangulare. Hyades. Pleiades. Vergilię . | ref: 4 |

| Gygantes rugitu asinorum exterriti . | ref: 4 |

| Hercules in Cancrum . | ref: 4 |

| Aquarius Ganimedes . | ref: 5 |

| Eridanus . | ref: 5 |

| Nondum uini usus Cecrope regnante . | ref: 5 |

| Orion currens supra fluctus . | ref: 5 |

| Ganimedes . | ref: 5 |

| terrena semper mixta miseriis . | ref: 5 |

| Orion . | ref: 5 |

| Sagittarius . | ref: 5 |

| Astrei et Aurorę filia . | ref: 5 |

| In Lero inuecti lepores . | ref: 5 |

| Orion . | ref: 5 |

| Currens super aristas . | ref: 5 |

| Lepus alios pariens, alios in uentre habens . | ref: 5 |

| Cetus cui exposita Ariadna . | ref: 5 |

| Lepus alios pariens, alios gerens . | ref: 5 |

| Orion a scorpione ictus . | ref: 5 |

| Capricornus . | ref: 5 |

| Venus et Cupido . | ref: 5 |

| Oenopion sub terra delituit . | ref: 5 |

| Coruus ex albo niger . | ref: 6 |

| Piscis notius . | ref: 6 |

| Canis . | ref: 6 |

| Ebriositas. Erigones. Boetes. Canicula. Orpheus interemptus, id est coruus expectans, donec in ficu fructus maturescant . | ref: 6 |

| Coruus pertusum habens guttur, dum ficus decoquantur . | ref: 6 |

| Chiron . | ref: 6 |

| Coruus ab Apolline missus . | ref: 6 |

| Chiron Herculis sagitas inspiciens, una de manibus lapsa pedem sauciat et perit . | ref: 6 |

| Argo . | ref: 6 |

| Circulus lacteus in cęlo . | ref: 6 |

| Ara in qua dii sacrificarunt priusquam Titanas inuaderent . | ref: 6 |

| Planetę . | ref: 6 |

| Canis uelocissimus . | ref: 6 |

Conclusion

The Repertorium is a text from another time and another mindset. It is also a dependent text. Therefore, it simply can not be understood without the books from which it is culled, without the structure which created it. So, to make the Repertorium worth editing, we should devise for it an edition which brings together Marulić's loci communes and the pages from which he selected them, his words and the handwriting which embodied them.

Moreover, the Repertorium is not a text for continuous reading. It is an information retrieval device, and because of that it lends itself easily to digital manipulation — to rearrangements and fragmenting — and to digital medium, which can connect the visual and the verbal, a single work and its many intertexts. Discontinuous nature of the text implies also that we can experiment with piecemeal editing — at first we could present in full encoding, with all pointers, not the whole thing but only the parts we are currently interested in (this is similar to the way Marulić himself compiled the Repertorium). Finally, a digital edition in cyberspace seems to me to be limited today much less by printing costs and physical constraints than by scholarly resources. Ultimately, the edition will depend on its editor's time and patience, attention and devotion, engagement and imagination.